Fictional heroes have been around since the dawn of storytelling, their stories relayed through the oral or written word, through art. Through tales of fantastic feats, sometimes historical and sometimes allegorical, a connection with the hero is usually made with the recipient of the story. There may be a trait or ability that we identify with and that hero becomes something larger than life, something with a heavy anchor in our minds, and we make a direct connection with the hero.

I must admit, I was a Superman/Batman guy. So, it was DC for me. But then my older brother explained the dark life of Peter Parker. Hello Marvel Universe. Spiderman was the first superhero who was flawed. I related immediately. Oh, not the web shooting out of my wrists, although Lord knows, I tried. But all of his problems?

Similar to Bruce Wayne he is obsessive, depressive, and overly stubborn. He is still psychologically affected by the death of his parents. He is haunted by the death of his Uncle Ben, and his mood swings can border on depression. He would probably save Mary Jane, Gwen Stacy, or his Aunt May even if it caused the death of dozens of other people.

Upon thanking him, he would then lament over what he had done. He can never allow himself to be happy. This often causes anxiety and depression, which leads to unhappiness.

Or, well, that’s what I think he feels because well, I could relate to his misery.

Boyhood Heroes

But then there are the real childhood heroes. The ones we see every day. The ones who are flesh and blood. The one’s who should never lose a game. Or the ones that have the coolest music.

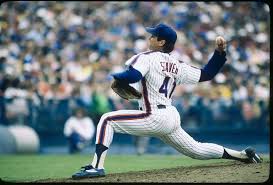

Tom Seaver, one of baseball’s greatest right-handed power pitchers, a Hall of Famer who won 311 games for four major league teams, most notably the Mets, whom he led from last place to a surprise world championship in his first three seasons, died on September 1st. He was 75. I cried.

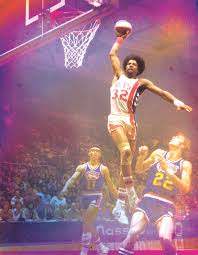

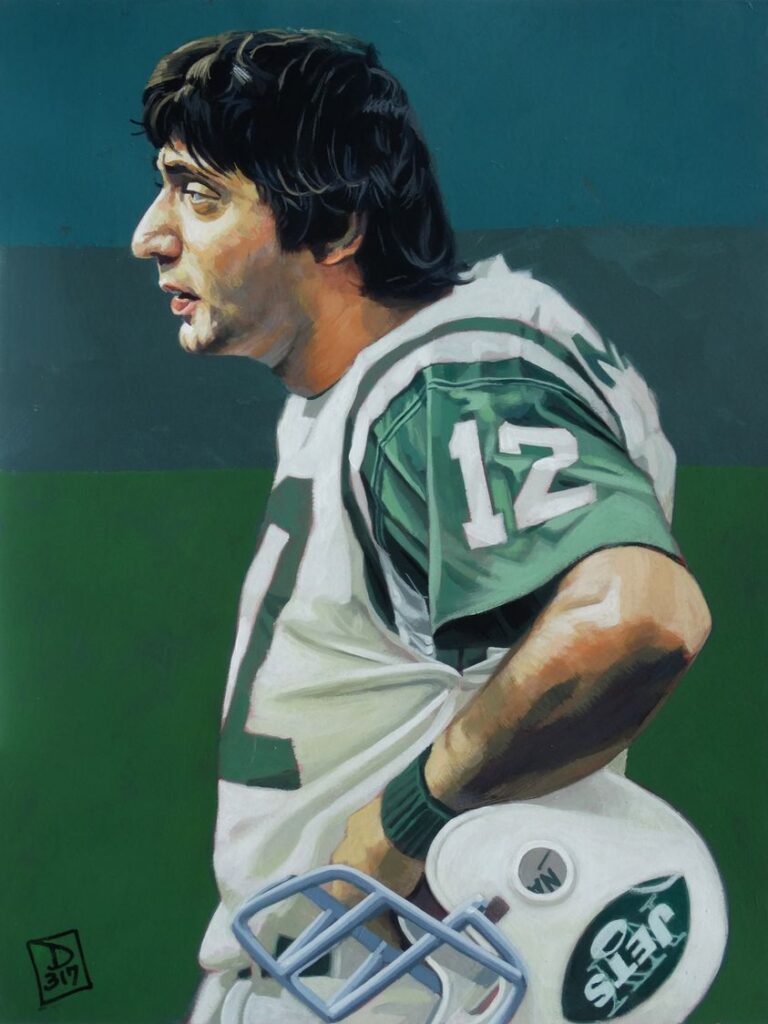

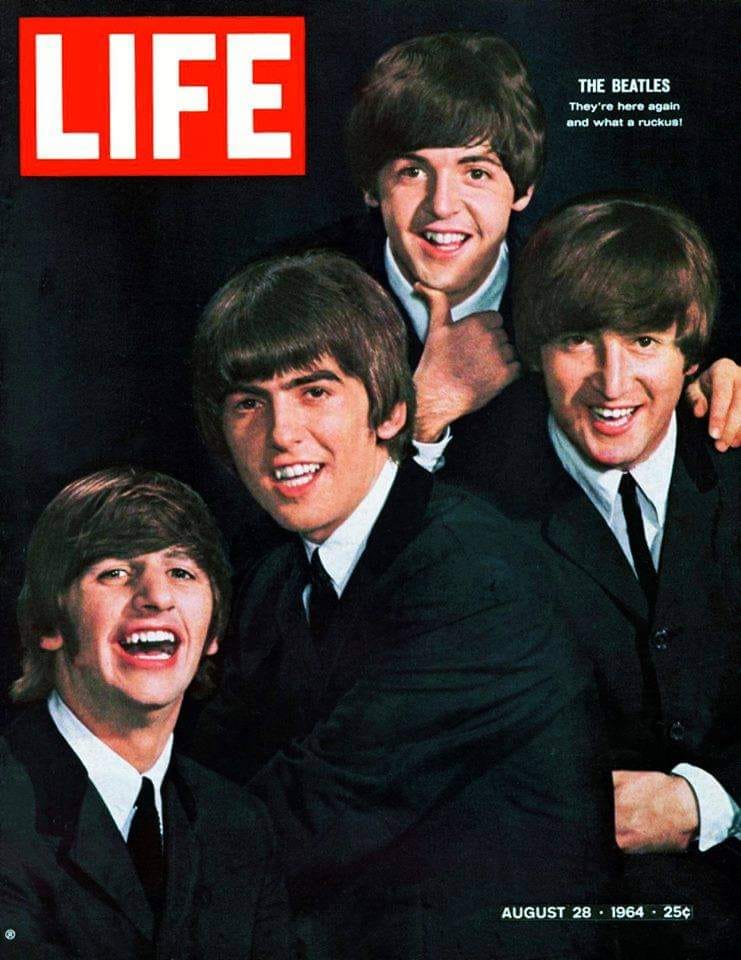

After my father, Tom Seaver, Joe Namath, and Julius Erving were my childhood heroes. That was in sports. Let’s sprinkle in The Beatles because, well, because they were The Beatles and just way cool.

I say that as someone who no longer attaches the word “hero” to a sports figure or musical group. Heroes are children battling life-threatening diseases. Heroes are first responders, people trained to run towards the danger I run away from. Heroes are those who give their own lives to save others. Heroes are teachers working for minimal pay to educate our children. Heroes are the people always there for you, no matter the cost. Yep, my dad fit that bill.

Of course, language is flexible and mutable. The original Greek “heroes” meant “protector” or “defender,” and every culture has heroes woven into their mythology. The ancient Greeks nearly filled an alphabet of heroes, from Achilles to Theseus.

I grew up with no Internet, no Sunday Ticket, no DirecTV. I read the Newsday sports section and studied box scores. I waited until the 11:00 local news to see highlights of a Walt Frazier steal or a Doctor J dunk (I used to have an ABA basketball with autographs of the first New York Nets ABA championship team led by Julius Erving, but somehow my ex-wife decided that since I wanted it, I would never see it again even though it was presented to me the day of my Bar Mitzvah), or a Tom Seaver fastball that saw him scrape his knee on the mound. As for Joe Namath, he was just, well, super cool.

It was comic books for 50 cents apiece with money from my newspaper route. I delivered an afternoon newspaper in the 1970s, Newsday, just before afternoon newspapers went into extinction. Most of my friends on the South Shore of Long Island were Mets fan and my hero, everyone’s hero, was the Franchise, Tom Terrific.

It was Strat-O-Matic baseball, the original fantasy league, with my friend Michael and all those box scores every day after school. West coast games were tough because we had to wait till the day after they were played to get a box score.

I still remember tearing open a bundle of papers, ripping out a sports section and reading about Seaver winning his second Cy Young Award. It was sometime around Halloween, 1973. Seaver was 19-10, which is not exactly a sterling won-loss record. (That was when 20 wins were the benchmark of greatness). But he led the National League in ERA (2.08), complete games (18), and strikeouts (251). I told you I was a sports geek.

I knew he was good. I knew the Mets were not. I knew, because my dad, finally over his beloved Dodgers moving out of his hometown Brooklyn, would tell me that Seaver had to pitch a shutout every time he took the mound because he could lose the game 1-0.

He deserved a better contract. The team was awful and as he was winning games 1-0.

Seeing Tom Seaver in a Cincinnati Reds uniform still evokes agita, pain and sadness. It would come to be known as the Midnight Massacre—the day Tom Seaver, #41, was traded away.

The cast of characters responsible for the trade are many, but the principals were Seaver, M. Donald Grant, the chairman of the board of the Mets, and the Daily News columnist Dick Young. We can trace the roots of the deal back to July 12, 1976, when a new Collective Bargaining Agreement was reached which, among other items, ushered in free agency for the first time. Seaver signed a three-year deal worth $675,000 making him the highest-paid pitcher in baseball, a distinction that would be very temporary. They reached his deal just a few months before the new CBA was adopted and was said to be a contentious negotiation between Grant and Seaver’s agent.

There was a reason I loved 1969. Woodstock. Abbey Road. Moon shot. The Jets. The Mets. The Knicks.

From 1969 on, Seaver was a celebrity — part of a new generation of sports heroes in New York. He starred along with Joe Namath of the Jets, who won the Super Bowl nine months before the Mets earned their championship, and Walt Frazier of the Knicks, who won the National Basketball Association crown in 1970.

My dad loved to watch sports. We had season tickets to the Jets (I placed that dreaded curse on my two sons; they are always rebuilding) so I watched Joe Namath when he was playing and on the sidelines when the offensive line did not block for him and wearing a full-length mink coat.

I cried when the Jets traded him to the Los Angeles Rams. But the word was maybe, just maybe, the league owed him one last chance at a title so we could watch Broadway Joe turn back the clock to become Hollywood Joe.

We had tickets for the New York Nets at the Long Island Arena in Commack and then the newly built Nassau Coliseum. There is no way to describe the joy in remembering Doctor J with that big afro and number 32 jersey lighting up the ABA night after night.

There is less joy in hearing the stories of why the Nets had to sell one of my childhood heroes to Philadelphia. The only piece of good news was that the Knicks turned him down. Thank God! I could not live with my hero on the team that would now be an enemy because of a merger.

Broadway Joe. Doctor J. And Now This?

And now, with the help of Google, here is a small synopsis of the day my world was shattered… again! (It’s no wonder I am so screwed up today).

They advised Tom Seaver to go over the head of management and talk directly with owner Lorinda deRoulet. She, Seaver, and McDonald worked out, in principle, a three-year contract extension as the trade deadline approached. However, before he signed it, Young wrote a suspicious column that intimated that Seaver was being goaded by his wife to ask for more money, supposedly because she was jealous that Nolan Ryan was making more money than Seaver.

The mention of his wife enraged Seaver, and while in a coffee shop in Atlanta, he phoned Met management to inform them the deal was off and to “get me out of here.” McDonald complied, and he traded Seaver to the Reds for pitcher Pat Zachry, minor leaguer’s Steve Henderson and Dan Norman, and infielder Doug Flynn. That night, the Mets also traded Dave Kingman to the San Diego Padres for Paul Siebert and Bobby Valentine, and Mike Phillips to the St. Louis Cardinals for Joel Youngblood. They would dub the trio of trades the Midnight Massacre.

Except for that miracle of 1969 or the second half of the 1973 season, the Mets were awful. They were a terrible organization who knew extraordinarily little about baseball.

Over the past 20 years, only one pitcher has reached double digits in complete games in a season (James Shields, Tampa Bay, 2011). Seaver pitched 231 complete games over 20 years with the Mets, Reds, White Sox, and Red Sox.

Yes, yes, yes, the game has changed. We now live in a time where there are lefty-on-lefty specialists who come in to throw to one batter in the middle of the fifth. The game has changed.

It’s always changing.

Dead-ball vs. live-ball, spitball and post-spitball, high mound vs. lowered mound, 100 years without a designated hitter and 50 years with one, segregated era vs. post-segregation. Who had the greatest peak years? Who had the best long career? It’s impossible to say where Seaver ranks among the all-time greats.

The 1975 Mets were such a bad team. They went 60-71 when Seaver was not on the mound and 22-9 when Seaver got a decision. I remember tearing open a bundle of papers, ripping out a sports section, and reading about Seaver winning his third Cy Young Award. I remember turning the pages with ink-stained fingers until …

There it was, the picture. Tom Seaver with his right hand raised three-quarter-arm, approaching release point, glove on left knee, right knee dragging in the dirt, biting his lip as he launched the whole of his 6-foot-1, 220-pound body toward home plate.

It was just like the poster I had tacked to the inside of my bedroom closet. My room was covered in team pennants leaving me no room to place that poster anywhere else.

Time to Grow Up and Put Away Childish Things

When they traded Seaver to the Reds in 1977, I was done. The owner of the Yankees had embraced this crazy new free agency and was overpaying for superstars to play for him. Unlike the Mets, he was embracing this new age, not denouncing it.

I had a meeting with my then 22-year-old brother, and we agreed. It was over. We were going to the dark side. It was fun. It was exciting. It was cool. Reggie. Thurman. Billy. Screaming. Fights. Excitement.

A few years later I imagined a kid tearing open a bundle of his version of Newsday on an afternoon in October 1981 and looking for the picture. I can imagine the kid wondering how Seaver — who was 14-2 with a 2.54 ERA in a strike-shortened, split season — did not win his fourth Cy Young. Fernando Valenzuela was something, but he was no Tom Seaver. Nobody was.

Arguments persist about whether it is physically possible for a fastball to rise, but I will swear that Seaver’s fastball climbed belt-to-chin. Later in his career, he added pitches (flop-curve! change-up!) and survived on finesse until he was 44. In 1992, he became a first-ballot Hall of Famer with 98.8% of the votes, a record that stood until Ken Griffey Jr.’s induction in 2016.

I was a Mets fan before the Miracle of 1969 — when Seaver won his first Cy Young and the Mets won their first World Series. I turned 8 the March before the Mets beat the Atlanta Braves to win the pennant that year.

Memories Seem Like Yesterday

The Hall of Fame announced that Seaver, who was suffering from dementia, Lyme disease, and COVID-19, will now warm up in another bullpen.

I got the news within seconds and e-mailed Greenie, one of my oldest friends and now living on the west coast. The most diehard Mets fan who, to this day, can still talk about July 7, 1973. That, of course, was the day George Theodore playing left field and Don Hahn in center crashed into each other on a Ralph Garr hit ball to left-center, causing bruised ribs for Hahn and a dislocated hip for Theodore, batting .259 at the time. It was more of the same old Mets for everyone else until “Ya Gotta Believe” and the Mets won the pennant.

But those days are long gone as I saw another childhood hero fall. My dad died nine days after my first son was born in the summer of 2000.

Joe Namath. The Doctor. Two of the four Beatles.

That’s it. Those are my childhood heroes. There will be no more.

Большинство людей сегодня используют интернет не столько для получения информации, сколько для покупок различных товаров, которые просто заполонили его. И здесь также можно найти запрещенные к продаже и незаконные категории. Но не в обычном поисковике по типу Яндекса, а в отдельной зоне, известной как Даркнет. Одной из площадок этой сети и является гидра, сайт которой мы и рассмотрим более подробно в этой статье. Потому, если для вас тема приобретения незаконных товаров актуальна, то вам материал будет полезен.

Большинство людей сегодня используют интернет не столько для получения информации, сколько для покупок различных товаров, которые просто заполонили его. И здесь также можно найти запрещенные к продаже и незаконные категории. Но не в обычном поисковике по типу Яндекса, а в отдельной зоне, известной как Даркнет. Одной из площадок этой сети и является гидра сайт ссылка, сайт которой мы и рассмотрим более подробно в этой статье. Потому, если для вас тема приобретения незаконных товаров актуальна, то вам материал будет полезен.

Excellent article. I am dealing with a few of these issues as well.. Wini Terrance Bakeman

Wow, wonderful blog layout! How long have you been blogging for? you made blogging look easy. The overall look of your web site is excellent, as well as the content! Nina Humberto Daryl

Thank you, Nina!

I love it when people come together and share views. Great website, keep it up! Leta Baillie Ruvolo

Thanks so much Leta.

You made several good points there. I did a search on the issue and found mainly persons will go along with with your blog. Reggi Shep Cletus Susanetta Marty Rossi

That’s terrific. Thanks Reggi!

This paragraph is actually a nice one it assists new web people, who are wishing for blogging.

Thank you Cassandra

I have read so many articles or reviews on the topic of the blogger lovers but this piece of writing is truly a good post, keep it up.

Thank you so much!