I read an article in Time Magazine. It talked about a Broadway show called “Sea Wall/A Life.” The writing in these separate monologues — played together on a double bill at Broadway’s Hudson Theatre — with solo performances by Tom Sturridge (“Sea Wall”) and Jake Gyllenhaal (“A Life”)had a common theme, death.

It said, “Meet Alex, a photographer on a holiday with his family in the south of France. Meet Abe, a music producer with a baby on the way. Two men – both fathers, husbands, and sons – take us on a journey you will never forget.”

It was two shows, Sea Wall and A Life, using the same set with a short intermission separating them. It ran for seven weeks last summer.

In Seawall, Alex envisions a journey for his young daughter — a gentle glide through a happy life, followed by a gradual and painless descent into the darkness of death. It’s the loss of this comforting myth that is, in part, what has Alex in despair. “A Life,” it said, “Swings erratically between Abe’s father’s ill health and his wife’s pregnancy.”

Woah, Woah. Woah. Stop the clock. I dropped the magazine on the bathroom floor. Yes, okay, I admit it. I read magazines in the bathroom. It beats the people who take their iPhones in with them and don’t wash it or their hands when they are done. (You know who you are).

But, back to the review. It got me thinking. This is the most honest I had ever been with myself.

Without picking up the magazine I read the rest of the review as it laid on the bathroom floor tile.

“Sea Wall/A Life,” it said, “Was the most stripped-down storytelling on Broadway. The quiet spectacle shows like these, is in the acting of tragicomedies of love and loss, young men’s stories about fatherhood and family, and about the hole that grief can blast right through a person’s center.”

Okay, I washed my hands, stopped for a moment to regain my composure, and Googled this thing.

My Lord. Let’s talk Death: sudden death, painful death, lingering death, accidental death, and whatever other kinds of death happen to come into the receptive minds of the guys who wrote these stories, playwrights Simon Stephens (“Sea Wall”) and Nick Payne (“A Life”). I can talk death all day long. I feel dead inside on most days. I feel lost and in such great anguish and pain. I feel lonely even when I’m with people. It would be nice to have my despair and pain eased for some moments. If someone could listen – I mean really listen and not judge. I sit and think Trent Reznor was correct when he wrote, “Everyone I know goes away in the end…I will let you down, I will make you hurt.“

Both shows take place on the same stone-cold set — two levels of solid brick walls. Both men reflecting on death.

I am fixated on death, depression, and misery so the story of “A Life” drew me in.

For twenty years I have tried to put some sort of logic to my life which has become an endless freefall. It started with quicksand and landed in an unimaginable dive in an endless fall. I have yet to hit bottom.

I did not understand it at the time but I slipped into a horrible depression. I was married to someone who was an emotional bully. I used to get depressed. With good reason looking back, because it was an awful life, never knowing what lies and accusations would come my way, and being abused when I walked into the house. Sounds completely uncanny to me now, but, it happened. There’s so much more to that story….that’ll do for another time.

I managed to cope just after my father’s death and my son’s birth even though it was a horrifically awful thing to have to come to terms with. But then, as everything started getting back to normal I felt as if I was falling into that dark bottomless pit from which I would never escape. It was terrible. I was scared. It was like walking around, blind, in a dark, damp scary tunnel, knowing that there were people having a wonderful life next door to me in the sunshine, but having no way of ever getting out of the tunnel, no way of ever being one of those people.

What “A Life” does is to blend mirth with grief as Abe, the character portrayed by Jake Gyllenhaal, relates not only the largely comic story of his child’s coming into the world, but also the more somber story of his father’s exit from it. This loss haunts Abe, in some ways paralyzes him.

And I could stop right there as that has been the epicenter of my world.

Let’s go to a quick backstory, skipping many of the sordid details.

In June of 1999, I married a woman with whom I was not in love. This typically happens for one reason. But no, she was not pregnant, and I was not doing the right thing.

This happened for the stupidest of reasons, I was weak, and she was a narcissist, which of course I did not learn or understand until many years of separation.

I was bullied into the marriage by the Narc and my parents. She wanted to be married in the worst way (to a Jewish man) and when my dad learned his mortality was catching up to him, he wanted his only unmarried child to walk down the aisle, allowing him to throw a wedding and a bon voyage party for everyone he ever knew.

My mother’s hairdresser met the Narc and said that we’d be perfect for each other. In all fairness to him, he met her once and she fit the criteria of what all Jewish mothers want for their sons. She was single and Jewish.

From the first time I phoned her, I knew there were issues. She asked if we could go out that night. I said that I had plans and she told me to cancel them.

We went out a few weeks later and my father asked how it went.

“She wants to get married,” I said.

“Okay. Bring her over for dinner and let’s talk about when.”

“I don’t love her. She just wants to get married.”

“I don’t care. I’m sick. I’m not getting any younger and I want more grandchildren before I go.”

The Narc bullied me into meeting my parents on the next date and my life was done. She moved into my apartment and slowly and methodically started working with my parents to plan a wedding while pulling me away from my friends and family.

“It’s not right Dad. It feels wrong. I don’t love her.”

“What is it with your generation? It’s not about love. It’s about growing up and showing responsibility. You’re a man. She’s a woman. It’s time. Enough with the nonsense. In my day, you got married, had children, had a job, and retired. You’re practically at retirement age. It’s time.”

“Dad, I’m thirty-seven. Not exactly ready for Medicare.”

Weeks before the wedding, my father told me, “It wouldn’t be so terrible if she walks down the aisle with a little baby bump, nobody would be upset.”

We found out about the pregnancy a few weeks after the wedding, when we also learned he was starting his third round of chemotherapy.

“Terrific,” I thought. “You’re leaving me after pushing me into this miserable life leaving me with a child.”

He survived the chemo. The oncologist even commented that he was surprised as to how well the treatment worked.

He could not wait for the baby to be born. He talked to me about looking for houses in the area and how he was going to give his grandson golf lessons.

I grinned. “What if him is a her?”

“He won’t be, but if it’s a girl, she’ll take golf lessons. That’ll be fine.”

With eight weeks to go in the pregnancy, my father was rushed to the hospital. He was intubated and hooked up to way too many machines to count.

He never regained consciousness. My mother sat with him daily, praying for a miracle.

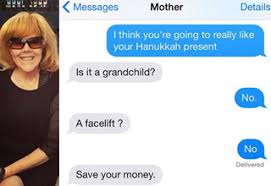

“Its been 47 years,” I heard her say one afternoon when she thought nobody was around. “How can you leave me? You waited Steve’s lifetime for him to get married and give you a grandchild and you’re gonna leave me here, like this? I guess you were finished.”

I wanted to cry. I was miserable. The Narc was upset that the focus of my family, as well as hers, was on my father. Not her.

I walked into my apartment late one evening after a particularly difficult day with my mother. I felt those steely eyes upon me. “When my sister had her kids, she was made to feel like a queen. I’m the maid. You don’t care. All you do is sit at that hospital with your family because they are more important than me. It’s always about your mother. I am your wife. I come first. What don’t you get about that?”

My mother kept him alive until Alex was born. He was beautiful. She cried. I cried. And when my mother asked if I wanted to go down the street for a slice of pizza so she could talk about what she needed to do, the Narc’s father said, “Go. We’ll be here with her until you get back.”

My mother knew she had to tell the doctors it was time to say goodbye.

“He needed to know that grandson number seven was alive and beautiful. Now he does,” she said between tears.

And that was it. She went home to think about the most horrific decision a wife could ever make.

I went back to the hospital and was ferociously beaten down by a woman who had given birth a few hours earlier to our son. She was livid that I would leave her to talk to my mother about pulling the plug on my father. “This was supposed to be about me, not you, you bastard.”

My mother decided to pull the plug two days after Alex’s Bris.

I was left wondering how this happened. The two most difficult emotions on earth, life and death. I had the opportunity to prepare for both, and I learned you can prepare for neither.

The song, The Living Years, by Mike and Mechanics, suddenly made me cry. I could not stop playing it as the Narc screamed at me that I was sick and masochistic.

“You are thinking about your father to hurt me. It about me. Not you.”

She removed the CD from my CD player and broke it in half, while visiting my mother, leaving it on my desk in my home office.

A red flag you say? Nothing made sense in my life from that point on.

Was I disrespecting my father if I seeked a divorce?

Could I live with myself if I did not see Alex every day.

Should I give Alex a brother, in case things go completely off the rails with his mother and me?

Was everybody right? Was she envious of everybody in my life? How could I live in such a world?

If it were a movie, I could see my father’s soul leaving his body on a cloud arriving in heaven and having the chance to see Alex. He too would be on a cloud and they would have the chance to speak.

Dad would explain everything, including why he had to grow up without his grandfather.

I look at old photographs of my dad and smile. I look at Alex and think that my love for him is equal to the love that my father had for his kids.

Funny how two people, one now a beautiful young man and a sophomore in college, and one so charming, caring, and silly will be forever linked while having never met on this planet.

As I said earlier, if it were a movie, angels would be singing. Since it’s real-life all I keep thinking about is how unprepared I was for marriage, life, and death.